Story by Nonye Ekwomadu

It was 3:45 PM on a Wednesday afternoon. Joyce sat in front of her small grocery store, known in Nigerian local parlance as “Provision” shop, selling her wares as well as waiting for her kids that had gone to school that morning. The house where she lived was an old one that boasted of four studio apartments. The edifice, painted green and cream colours, stood on a road, Ramoni Street, coincidentally named after the bus stop where it tapered off into Lawanson Road. The street was on the right side of the dual carriageway if one was coming from Ijesha community. A sleek Lexus RX 450h 2019 model glided down the road and pulled to a halt in front of her store. Obviously, someone had flagged down the rider, and the person walked up briskly to the automobile. The driver’s windscreen slided down and the occupant, a fair skinned woman, began to talk with the woman who had stopped her, a lady as well. Joyce, who was donning a blue t-shirt with inscriptions, atop a pair of black knee-length denim shorts, cast the duo a warning look, signaling they should back-off her domain. Possibly, she anticipated that the driver ought to move her car elsewhere for whatever discussion they were having. Conversing animatedly, throwing in occasional bouts of laughter, the women hot seemed not to take cognizance of her displeasure as they talked animatedly. By now, Joyce was fuming as she stood hands akimbo, glaring at them. Her reality was that she couldn’t and wouldn’t do jack to the car owner, whom from every indication, was way higher than her in social status. Seemingly defeated, Joyce hissed aloud to then- hearing and exclaimed, “Vanity upon vanity!” The lady who was speaking with the car driver informed her companion of Joyce’s utterance. Both of them burst into laughter at that instant. “Adaobi”, the car occupant called the woman talking with her, “Give that excuse of a woman a glimpse of what you think of her.” Adaobi turned to Joyce and uttered,

“Hey woman! Is poverty any better? Isn’t it a sort of vanity as well? I Uju, let’s not pay attention to this woman. She looks frustrated, for this singular reason, I won’t banter with her.” They resumed their conversation. However, at approximately ten minutes afterwards, the woman joined her friend in the car and they drove off, giggling as they cast Joyce glances filled with mockery. When they had left, the woman also selling household stuff next to Joyce started talking to her.

“Isn’t she the owner of that gigantic house down the road? She’s that doctor whose husband is an accountant, right?” Joyce’s neighbour, mama Ayo, who sold domestic plastic containers, asked when the car had left the vicinity. Lost in thoughts, Joyce nodded in acquiescence to her interrogations.

“Big deal! So, because she’s a doctor, she won’t let us be?” Joyce asked her. Mama Ayo merely shrugged like someone who had lost all hopes in life.

“She’s so full of herself. Ha! Na wa o.” Mama Ayo Reiterated. “Over my dead body if my daughter doesn’t become a doctor!” Joyce blurted out defiantly. Mama Ayo peered at her with a bemused look,

“Do you mean your daughter, Kaima?” Joyce nodded. Instantly, the voices of a bunch of youngsters intruded into their chitchat. A teenager with two other toddlers crossed the plank that covered the gutter in front of Joyce’s shop. “Good afternoon mummy. Good afternoon ma.” Kaima greeted her mom and mama Ayo too, guiding her siblings into her mother’s shop.

“Welcome my children. No, no, Kaima, take them inside the house. Your dad is at home. Tell him to help you all with your homework.” Kaima ushered her brothers towards their apartment. Their father was reclining on the sofa in the tiny living room. Kaima curtsied as she greeted him. The fourteen years old lass took the younger children, Ik and KK (Ikechukwu and Kenechukwu), a set of twins, into the inner chamber. When they had changed their clothing, Kaima brought out the twins’ assignment and passed it to their father. He glowered at her. Kaima rose up in defence, “Mummy asked that you assist us with our homework.” “Why do your teachers derive joy in giving out assignments they themselves cannot solve? So, you mean to tell me after going out to hustle for our daily bread, you people still expect me to start wracking my brain trying to solve this riddle of a homework. Why did I send you to school? Are you not supposed to be the one teaching me and not the other way round?”

He stretched forth his hands to have a look at the book she was holding, exclaiming,

“Ha! Quantitative reasoning!” “But dad, it’s for nursery 1 class!” “Ehen, then go and solve it if that be the case.”

“Dad, I have my personal homework to do.” Kaima replied sulkily. Her father looked unperturbed. “They didn’t teach us this type of maths during my time.” His daughter appeared shocked, “Does maths change with years?” “Oh, so you weren’t informed. Just like in my own time when there was no mobile telephone, no internet so also, we didn’t do this type of maths. There are so many things in circulation now that weren’t in existence when I was growing up.” Kaima chuckled, giving him a jeering look, “So, it’s not out of place to call you old school then.”

“Taa!” Martins, her father chided. “I’ll warn those teachers of yours to desist from giving you any assignments they didn’t make you understand and resolve on your own. What am I paying school fees for? After spending through my nose, they still expect me to go through this kind of hassles by giving you trash all in the name of homework. Kamnu kwa.” Joyce walked in, “Are you done with the homework?” Silence fell in the room as she asked, taking a seat close to her husband.

“Marty, I’m talking to you.” “I thought you were speaking to Kaima.” Martins answered. “No. I’m referring to you.” Joyce insisted.

“What did you say happened?” Asked Martins. Joyce gave him an exasperated glance, “Don’t tell me you didn’t hear what I asked.” “Oh, I’ve forgotten you’re Queen Elizabeth or better still, Margaret Thatcher? Hence, I must pay obeisance while talking to you.” He gave her a mock bow while still seated.

“Come off it, please! Papa Kaima, have you helped the kids with their homework!” She was practically screaming now. “What happened to you that you can’t do it yourself?” He glared at her. “You’re the man of the house, so it’s your responsibility.” Joyce charged fiercely.

“Goat has eaten palm fronds off my head.” Martins exclaimed and whistled as he looked on at her, flabbergasted. “The goat can eat off the palm fronds off your mouth for all I care.” Hissing, she dragged the book from kaima’s hand.

“My dear daughter, a doctor ha the making, I trust you can do this maths, after all, you’re science inclined in school.” Joyce was smiling at her.

Kaima scratched her head, puzzled as she stalled, “No, mom, I’m in arts department. I

want to be an artist.” Joyce flopped against the sofa’s headrest in disbelief. “My village people has finally got me. What did you just say? Did I hear you say you want to be an artist, or am I dreaming?” “Mom, I can draw very w-” “Mechipu onu gi there!” She flung the book aside, “I’m going to kill myself if you don’t become a doctor… or better still settle for a profession more tangible. When I was a child, I longed so much to become a doctor but my parents didn’t have the resources,” Martins interjected, “You forgot to mention that you didn’t possess the brains, not then and not even now.”

Joyce scowled at him, “Martins, see eh, be careful because it’s either you kill me today or 1 kill you. Just avoid me, at least for today.” Martins faced Kaima and interrogated

“By the way, Kaima, what’s with this artist you want to be? Whatever happened to engineering, nursing, or let’s just say, careers like accounting, law and other good ones?” “But dad, I can draw and paint fantastically!” Kaima bursted out. “Oh, really? Taa! Don’t be deceived because you think you have numerous hobbies. Do you know all the so many things Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala or Oby Ezekwesili can do? But did they get confused along the line? People might have a wide range of hobbies but the fact still remains, they shouldn’t get distracted along the line. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala might be a fantastic cook at home. Does it then imply she turns into a chef publicly? I’m certain it wouldn’t look good on her.” Kaima’s countenance didn’t look like she was convinced. Her dad cleared his throat of phlegm and said with a note of finality, “Just so you’d know this, I won’t be a part of sponsoring any education that involves studying any nonsensical course in the university.” Kaima kept gazing at him in bewilderment.

*****************************

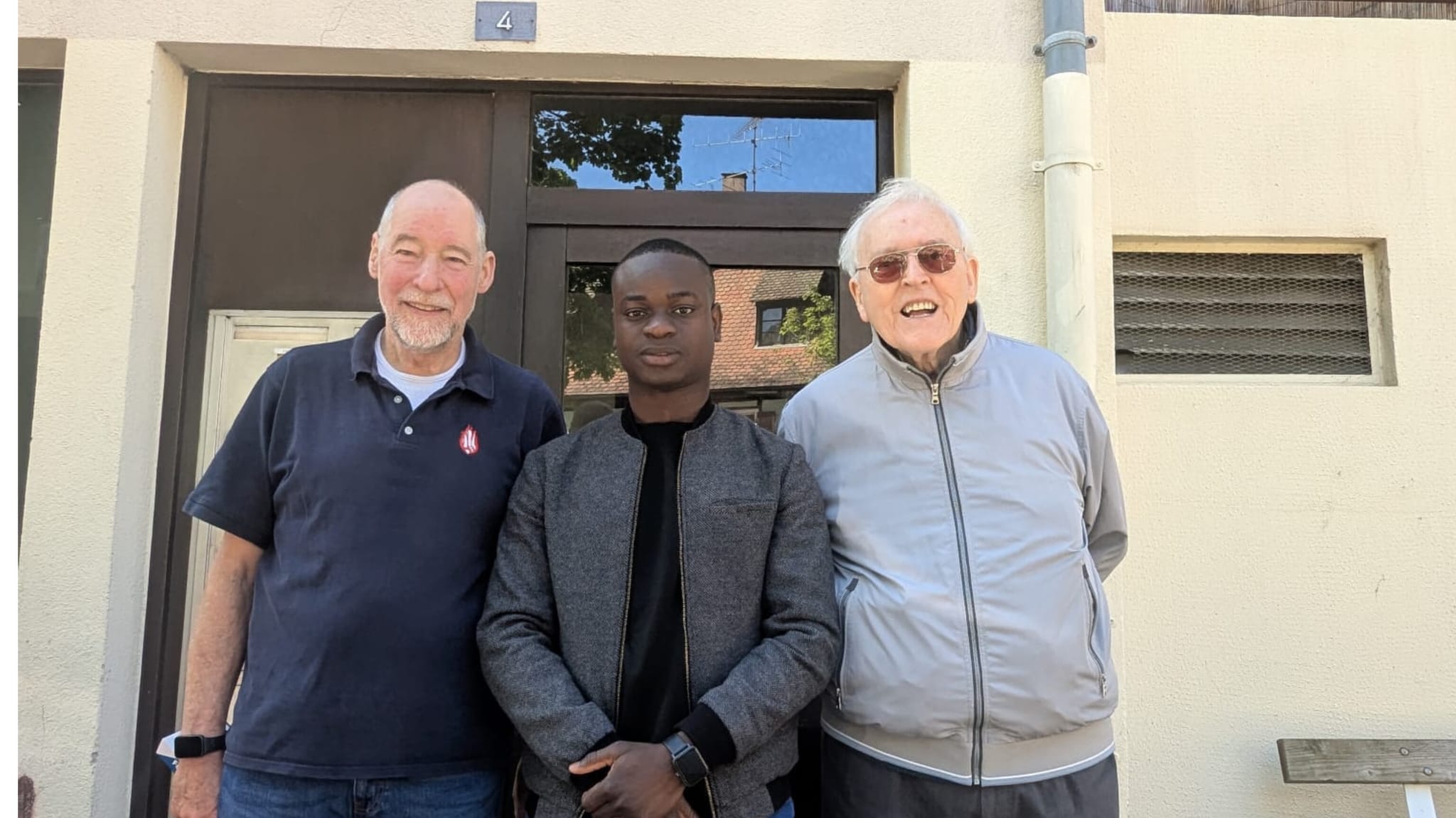

“Lekan! It’s really been a while!” The duo shook hands and hugged. “Boy, you can say that again! Jide, thank goodness for social media, otherwise, how else could we have kept in touch?” “Where is your wife, did you come with her?” Jide inquired as both men appraised each other. “For where. Na oyibo na. When I told her I was going to hang out with my long time buddy and that we are going to eat local stuff, she turned up her nose in irritation. I didn’t bother asking her if she was game, had to let her be.”

“I bet she won’t be able to blend into this kind of our old life style” Said Jide. Lekan began, “Guy, you see eh. Na wetin I wan chop be this, suya wrapped in old newspapers, akara wey dem tie inside paper, amala ati ewedu, the list is endless.”

Jide laughed out loud, “One would have thought living in the US for this long would have changed you…”

“Na who talk that thing?! You dey whine me ni! Nija for life. There’s no way I can abandon Nigerian dishes.” Lekan replied, “Let’s start from Obalende, that’s why I asked you not to come driving down here in your car, but rather you should use an

Uber. Off we go then.”

They got into Lekan’s ride and drove away. Both fellows had been pals since their elementary and high school days and had maintained the friendship even when Lekan relocated to the United States of America to go to college. He graduated from the university having studied fine and applied arts, got a job and married a Caucasian American, who was also an artist and owned a big art studio in New York City. The union so far, had produced a three-year-old boy. Back in Nigeria, Jide too was done with higher studies and was working with an IT firm, married with a couple of kids, a boy and a girl, aged five and two respectively, Jide had always been this dark, five footer, sturdy chap while Lekan inclined towards a lighter skin tone, 5 feet 10 inches tall precisely, lanky with a boisterous nature.

****************************

“Kaima Okoro, your attention is needed at the principal’s office.” One of her school’s prefect came to her class to announce. Her heart skipped a beat as she rose from her chair, pushing her desk forward so she would have enough space to go out. She hadn’t balanced her school fees although, her parents promised to do so by the end of that month. Yesterday, she received six strokes of the cane for not being punctual to school; her palms were yet to heal from the pangs of the lashing. Now, she was going to be flogged for the umpteenth time. How on earth was she going to bear this again? Tears began to roll down her cheeks. The liquid glistened on her dark shiny skin as she shook her head while trying to stop her eyes from watering further, her plaited hair dangling in the same motion with her head. Her stature was commensurate with her age, although she wasn’t the prettiest girl in the school, if push came to shove, she stood a good chance of vying for the crown for the most beautiful girl among the bevy of damsels among her peers and contemporaries.

With gentle purposeful strides, Kaima headed to the office of the head of school. While on her way, her left foot struck a stone buried halfway in the earth and she remembered the fables her paternal grandmother used to narrate to them. If one hit a left foot against an object, it symbolised an omen. But if it was a right foot then, it was good luck. She sighed, resigning herself to fate. Que sera, sera; what will be, will be. At the principal’s reception room, she met other students whom she wasn’t aware what business they might have with the institution’s head. “Hey girl, what’s your name?” Asked the secretary in a loud voice, giving her a cursory look.

“Okoro Kaima, ma.” The secretary ran a quick look on the sheet of paper she was holding, “When are bringing your balance?” “My parents said end of month, ma.” “Which month?” “This month, ma.”

“The principal is waiting for you. Go in and tell her yourself.” Her heart began to race erratically as she stood up and made for the door leading to the office. Kaima knocked softly and a voice requested that she should go in. She turned the knob, pushed the door open and stepped her feet, covered in rubber sandals, into the office space. “Good morning ma.” Kaima greeted and stood facing the woman. There was a visitor seated on one of the cushion chairs at her extreme right. “Good morning, how may I help you, please?” The principal probed. “Yes ma. A prefect informed me that you requested to see me?” “What’s your name?” “Ma’am, the name is Okoro Kaima.” The principal’s face broke into a smile.

“And why did it take you ages to get here?” Kaima clasped and unclasped her hands, fidgeting, not responding to her question.

“Mr. Bamidele,” the head teacher turned to the stranger, “Here is our Kaima. Kaima Okoro.” The person she was referring to, beamed with smiles, got up and walked towards them, unfolding a long sheet of paper in his hands. “My name is Mr. Bamidele, I stumbled on this lovely piece. I guess it’s your examination script.” Kaima peered at the paper he was showing her and recognition hit her. “Yes sir, it’s mine, I drew this a long time ago, during one of our exams.” “But madam,” referring to the principal, Bamidele continued, “Why on earth don’t you store stuff like this, rather than discarding them?”

The principal scratched her head in perplexity.

“We don’t want everywhere littered with papers so, we mostly do away with them.”

“These are the kind of talented people we are looking for. Kaima, funny enough, I stumbled on this drawing of yours when I hung out with my friend. This sheet of paper was used to wrap akara for me at Obalende. How did exam scripts used in Lagos mainland get to Obalende, Lagos Island, Mrs. Ochuko?”

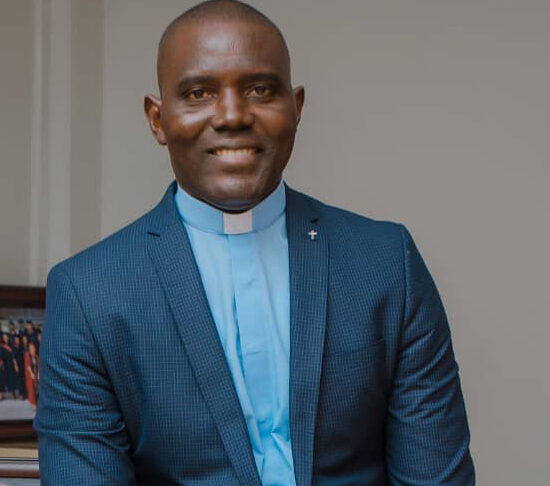

“I think some of the teachers usually sell them.” She answered candidly. He nodded, “Kaima, let me continue with my tale. I and my wife are artists based in New York city in the United States of America. We are committed to discovering people who are good in arts, so we could groom them to better their lots and to ensure that art and craft don’t go extinct. If we sponsor them overseas, they continue with their studies if they aren’t yet done with it in their home country. After studies, they get to work with us for two years, of course we have a contract pertaining to that. After which they can go elsewhere or do whatever that suits them. Can I get to see her folks?” The principal was already grinning from ear to ear. “Why not?! Now or when?” “Now, if you don’t mind, please.”He said.

Mrs. Ochuko, the principal jumped to her feet and picked up her handbag. Kaima couldn’t make head or tail of all what have been said. “Hmm, I suggest we go in my car, so I can head home from there.” “Mr. Bamidele…” Mrs. Ochuko began, “Call me Lekan.”

“Alright Lekan, em… there’s so much insecurity in the country presently, hence, let me bring it to your notice that I’m informing my colleagues and superiors about this movement.”

“Wow, that’s great! Supported. It’s a wise step to take. I would be disappointed if you didn’t take precautionary measures in the face of all the negative news that have been

in the air lately.”

Mrs. Ochuko nodded and beckoned on them to proceed to the door. Seated in their apartment, Lekan broke to Kaima’s parents the news he had shared with the principal. Martins whose work leave would terminate that week, was at home when the visitors came calling. He asked Lekan to repeat what he had just told him and he did. He requested again that he narrated the story once again. Joyce tapped him on the hand to stop being silly. Puzzled, Lekan asked if he was hard of hearing, Joyce shook her head.

“Mr. Americana,” Martins began, because Lekan spoke English with American slur. “Are you sure of what you just said?” Lekan was really amused with his behaviour, “For the records sir. I wouldn’t leave everything I’m supposed to do, come down here all the way from Ikoyi to crack jokes with you.” “Nne Kaima, pinch me biko because, it seems like I’m dreaming.” Lekan started laughing, “You’ll really make a great actor, a comedian

exactly.” “On a more serious note, if there’s an opening for an actor, kindly recommend me. The way I am now, am I truly living?” “Let’s finish with your daughter’s business.” Lekan urged. Martins, donning a serious countenance, sought more confirmation, “Do you actually mean what you said about my daughter?” “Dead serious.” Lekan enthused.

“Hey, Chukwu Abiama!” He sprang up from the chair but his wife clutched his hand.

“Why is he like this?” Lekan was laughing as he asked. Joyce answered him. “You won’t understand sir, no concrete good tidings has ever come his way. It’s mostly negative news of death in the family and so on. Sir, if poverty has ever dealt with you then, you’ll get my drift. That’s when you’ll understand why he’s acting this way.”

“Are you going to take my daughter to America?” Martins asked. “Yes of course, if you permit.” “If I permit?” He paused and continued, staring at Lekan like a drunk, “You see this my daughter,” Lekan nodded in the affirmative with anticipation, “Take. I dash her to you!” “Oghene bikooo!” Mrs. Ochuko who had been quiet all this while exclaimed. She couldn’t help but chip in, Martins’ demeanour was unbecoming. “Daddy Kaima, it’s okay o!” Joyce added.

“What about the acting we talked about?” Martins fired at Lekan.

“I doubt if you’ll qualify. America is quite advanced in terms of the calibre of movie actors they need. Since your daughter is a minor, it therefore implies, that onte of her parents will have to go with her.” “It’s going to be me since I’m the mother.” Joyce concluded quickly with finality. “And who looks after the children when you’re gone? Are you out of your mind?” Martins charged at her.

“This shouldn’t be an issue. I can sponsor the whole family.” Lekan offered. Husband and wife gazed at each other and burst into tears. It took them awhile before Martins regained composure and then he spoke. “Village people, ntoor! All the people that have scorned me in the past, chili ise!” He spread out his palms like he was bidding someone farewell. “I advise parents to encourage their children in whatever profession or career they choose in life. Parents should also assist their kids to discover what they have a flair for. Let their abilities be the guiding force in their chosen profession. Peace.”

THE END

Leave a comment